What most of us don't think about, or today may even know about, was very literally a Cartoon War with Max Fleischer.

.

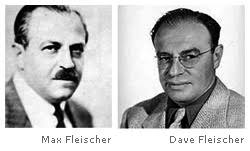

Max Fleischer born July 19, 1883 in Karkow, Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary.

“Rotoscoping” is a process of creating an animated look to a picture by tracing and inking onto each individual frame of a live action movie. The process was used in the 1968 “Beatles” animated classic “The Yellow Submarine” and

Ralph Bakshi would use the process extensively from 1976 to 1981 in films such as “Wizards” and his acclaimed version of “The Lord of the Rings.”

The process was still being used in 2008’s independent film “Sita Sings the Blues” by American Artist Nina Paley 94 years after the Fleischer Brothers invented it.

The old East Coast operations except for a few stubborn old timers, like Max, were closing shop by either moving west or just stopping production. This included those located in the middle of the country like Disney and Paul Terry. In time even the money backers would relocate to that growing Housing Community called “Hollywoodland”. As a sign on the side of a mountain overlooking the business district proclaimed.

As I wrote the Fleischer Brother’s invented a sing-a-long cartoon where the audience was told to “Follow the Bouncing Ball”. At first in the silent era an employee in the theater held a glowing ball on a stick to lead the audience. Eventually the ball became part of the actual cartoon.

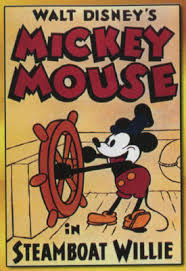

When you ask most people what was the first sound movie they will probably answer Warner Brother’s 1927’s “The Jazz Singer” starring Al Jolson. When you ask them what was the first sound-synchronized animated cartoon they will answer Walt Disney’s 1928 “Steam Boat Willie” starring Mickey Mouse. However, they would all be wrong in both cases.

A side note to what happened in 1934 to the Fleischers and others. Here are two examples of avoiding Hayes Office problems. Alfred Hitchcock found a way around the code for a scene in 1960’s “Psycho”. Actually he did it on purpose to get even with The Hays Office's interference in his productions. Up until that film you might see a bathroom sink or shower, but you never saw a toilet. Showing that particular item was a major no-no under the code. Obviously people just didn't need them, or knew what they were used for. Anyway, “Hitch” had a scene deliberately rewritten in "Psycho" showing Janet Lee ripping up documents and then flushing them down the toilet. There was no way around the scene as it was critical to the story line. So “Psycho” became the first film to show a complete bathroom under the Hayes Office Code enforcement and Hitchcock laughed all the way to the bank. Cecil B. DeMille also was able to get around the code by making all those "biblical" epics. Nobody including Will H. Hays would attack a motion picture based upon the bible even if it was filled with sex.

As I wrote earlier ex-Disney Animators Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising under their contract to Charles Mintz were now working at Universal Studio’s making the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series. In 1930 the two freed from their contract to Mintz moved to Warner Brothers to work under Leon Schlesinger. Sclesinger hired them because of the strength of the character Bosko the two had created back in 1928.

Their first project was to go after Walt’s successful “Silly Symphonies” and the ex-Disney animators created the first of the “Looney Tunes” cartoons. The name Schlesinger chose “Looney Tunes” was a direct parody of the name “Silly Symphonies”.

However, after three years the two would leave Warner’s and go to work at the Van Beuren Studios making cartoons for RKO Pictures. One additional year later the two moved again to MGM and began a series of Bosko cartoons as they had retained the rights to the character.

In 1932 Betty Boop became so popular that Max Fleischer was recognized as Walt’s major competitor and the feud gained momentum. Disney was concentrating on two series only. One was “Mickey Mouse” and other the “Silly Symphonies” that Leon Schlesinger was going after. What nobody knew at the time was the Walt had a plan and his first true dream for the future of animation and the Disney Brand. Since their creation Walt Disney had been using the “Silly Symphonies” as an experimental area in cartoon characterizations.

Part of Walt’s planned characterizations went into “The Three Little Pigs” released May 27, 1933. The cartoon would become the most successful in animation history and contained that catchy song “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” The short was so successful with audiences that some theaters ran it for months without let up. The depression era audiences loved the pigs and their song. Animator Chuck Jones said, "That was the first time that anybody ever brought characters to life [in an animated cartoon]. They were three characters who looked alike and acted differently" and that was what Walt was after.

What would cause the second major run in with Paramount Pictures for the Fleischer’s and dubbed “Disney’s Folly” by the media was announced in the New York Times by Walt Disney in June 1934. The newly created “Walt Disney Productions” was going to make the first full length cartoon feature based upon the story of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”.

However, Walt’s wife and his brother Roy had little faith in his project and they attempted to talk him out of it. Walt had told the press his estimated cost to make the animated film would be approximately $250,000.00. He would have to take out a loan on his home and use other measures to help pay for the project that would not cost his estimated $250,000.00 to make, but at end of production the cost reached $1,488, 422.74.

Part One:The Combatants:

Max Fleischer born July 19, 1883 in Karkow, Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary.

Walter Elias “Walt” Disney born December 5, 1901 in Chicago, Illinois.

Their Seconds, Where Their Brothers:

Max's:

Dave Fleischer born July 14, 1894 in New York City, New York

Lou Fleischer born May 18, 1889 in New York City, New York

Walt's:

Roy Oliver Disney born June 24, 1893 in Chicago, Illinois.

Part Two: A short Back Story:

You will be reading about two Animation Studios located on opposite ends of the United States. Disney in Los Angeles and Fleischer in New York City and finally in Miami Beach.

In 1914 Max Fleischer and his brother Dave made their first cartoon in a process they would obtain the patent for in 1915 called “Rotoscope”. This process would be used for the first five years of the “Out of the Ink Well” series that starred Ko-ko the Clown and Fitz the Dog. Music was provided composed by Lou.

Ralph Bakshi would use the process extensively from 1976 to 1981 in films such as “Wizards” and his acclaimed version of “The Lord of the Rings.”

The process was still being used in 2008’s independent film “Sita Sings the Blues” by American Artist Nina Paley 94 years after the Fleischer Brothers invented it.

In 1921 Max and his younger brothers Dave and Lou established “Inkwell Studios”, or “Out of the Inkwell Films” as a result of the success of their Ko-ko the Clown shorts. Ko-ko was actually designed around Dave who had worked as a clown for a while. In May 1924 Max would invent the “Follow the Bouncing Ball” cartoons where the audience sang along with the words on the screen and strangely this would eventually become one those events in the “feud” as Walt Disney’s would view it. Even though it wouldn't involve a Disney film until four years later. So let’s take a look at Walt’s early years.

His artistic career began in Kansas City, Kansas in 1919 drawing political cartoons for a local newspaper. At that time he was still thinking about becoming an Actor. Imagine the loss had that happened?

Roy Disney was working at a local bank and had a colleague who was able to get Walt a better job at the Pesmen-Rubin Art Studio creating advertisements for newspapers, magazines and movie theaters. It was at Pesmen that Walt met Ubbe Eert Iwerks (Ub Iwerks) who would always be his best friend. Fate had entered his life and the two mean would create an animation studio together that would soon go under, but the groundwork for Walt’s future was set firmly in place as a result.

Roy Disney was working at a local bank and had a colleague who was able to get Walt a better job at the Pesmen-Rubin Art Studio creating advertisements for newspapers, magazines and movie theaters. It was at Pesmen that Walt met Ubbe Eert Iwerks (Ub Iwerks) who would always be his best friend. Fate had entered his life and the two mean would create an animation studio together that would soon go under, but the groundwork for Walt’s future was set firmly in place as a result.

After that business failed Disney bounced around doing odd art jobs until May 18, 1922 when he opened “Laugh-O-Gram Studio” and with Ub Iwerks created the first of the “Alice Shorts.”

The series began to establish Walt Disney as an animator, but this studio also failed as his debt mounted and so Walt was force to declare bankruptcy. ”. The “Laugh O-Gram” studio consisted of Ub Iwerks and animators Fred and Hugh Harmon and Rudolf Ising. Names that would eventually become famous in the world of animation.

The series began to establish Walt Disney as an animator, but this studio also failed as his debt mounted and so Walt was force to declare bankruptcy. ”. The “Laugh O-Gram” studio consisted of Ub Iwerks and animators Fred and Hugh Harmon and Rudolf Ising. Names that would eventually become famous in the world of animation.

Walt’s determination to succeed took hold, or maybe a little stubbornness and he convinced Roy that they were located in the wrong place. He believed that like the movie industry the future for the animation industry was Hollywood, California. Walt would also convince Virginia Davis the star of the “Alice Shorts” and her mother to come along too. So also did Iweks and Ising after their own failed attempt to start a studio when “Laugh-O-Gram” went bankrupt. The Harmon Brothers decided they would go west with Walt and Roy. So the entire group left Kansas City for Los Angeles. The end result was the establishment of “The Disney Brother’s Studio” on Hyperion Avenue in the Silver Lake district. The stage was now set for the supposed “Animation Feud, or War” as some have described it.

Part Three: 1924 through 1929 “Silent Shorts to Sound Cartoons”:

For exactly three full decades starting technically in 1924 with those “Bouncing Ball” cartoons. Walt’s created hatred of the Fleischer’s would last. That same time period would also see the rise of the Disney Brothers and the fall of the Fleischer Brothers. Creating animosity within Max toward Walt’s success as a chain of events would go against him and his brothers.

The first mistake the Fleischer’s made was keeping their studio in New York were they had started. At the beginning of the Motion Picture Industry in the United States everything was based either in New York, or New Jersey. The East Coast with the major population centers of the time with cheap labor. However as Walt had realized the entire Motion Picture Industry partly for the all year round climate were moving to Southern California and expanding. That California sunshine was needed for silent films which were shot mostly outdoors for lighting the sets even in indoor scenes.

For exactly three full decades starting technically in 1924 with those “Bouncing Ball” cartoons. Walt’s created hatred of the Fleischer’s would last. That same time period would also see the rise of the Disney Brothers and the fall of the Fleischer Brothers. Creating animosity within Max toward Walt’s success as a chain of events would go against him and his brothers.

The first mistake the Fleischer’s made was keeping their studio in New York were they had started. At the beginning of the Motion Picture Industry in the United States everything was based either in New York, or New Jersey. The East Coast with the major population centers of the time with cheap labor. However as Walt had realized the entire Motion Picture Industry partly for the all year round climate were moving to Southern California and expanding. That California sunshine was needed for silent films which were shot mostly outdoors for lighting the sets even in indoor scenes.

The old East Coast operations except for a few stubborn old timers, like Max, were closing shop by either moving west or just stopping production. This included those located in the middle of the country like Disney and Paul Terry. In time even the money backers would relocate to that growing Housing Community called “Hollywoodland”. As a sign on the side of a mountain overlooking the business district proclaimed.

As I wrote the Fleischer Brother’s invented a sing-a-long cartoon where the audience was told to “Follow the Bouncing Ball”. At first in the silent era an employee in the theater held a glowing ball on a stick to lead the audience. Eventually the ball became part of the actual cartoon.

When you ask most people what was the first sound movie they will probably answer Warner Brother’s 1927’s “The Jazz Singer” starring Al Jolson. When you ask them what was the first sound-synchronized animated cartoon they will answer Walt Disney’s 1928 “Steam Boat Willie” starring Mickey Mouse. However, they would all be wrong in both cases.

The first sound-synchronized film was “Oh, Mabel, Mother, Pin a Rose on Me” in May 1924 by the innovated Fleischer’s in the “Phonofilm” sound-on-film process by Lee DeForest. This system recorded the sound onto the film as parallel lines. These lines photographically recorded electrical wave forms from the microphone which would be converted into actual sound as the film was projected on screen.

The use of DeForest’s process would be further refined by Max and Dave into their “Follow the Bouncing Ball” series featuring Ko-ko the Clown and music composed by Lou. Their second cartoon was “My Old Kentucky Home” in April of 1926 which innovatively was the first attempt to synchronize animation with dialogue. This may not seem like much, but Disney after releasing “Steamboat Willie” to much praise actually attempted to have any references to these early Fleischer works kept out of reviews. Walt WAS the inventor of the synchronized sound cartoon and not Max and Dave. The feud was on. Unknown, at the time, was the truth that “Steamboat Willie’s” sound-in-film system called “Cinephone” allegedly invented by Pat Powers was in reality Lee DeForest’s “Phonofilm”. Powers never obtained permission to copy the patented process. Disney found out later and this affected his relationship with Powers. Although he still claimed he invented the process.

It should be noted that “Steamboat Willie” came out in November of 1928, but in the preceding month on October 14th Paul Terry’s sound cartoon “Dinner Time” had been released. Walt said nothing about Terry’s film and to him it never existed.

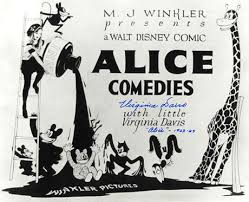

Back tracking when Disney moved west his number one output was the “Alice Shorts". In which a real young girl interacted with animated characters. The first one “Alice’s Wonderland” was released in 1923 and the series would continue through 57 shorts and four actresses until “Alice in the Big League” on August 22, 1927. However, the cost and technical restrictions were the reasons the series was finally stopped.

Back tracking when Disney moved west his number one output was the “Alice Shorts". In which a real young girl interacted with animated characters. The first one “Alice’s Wonderland” was released in 1923 and the series would continue through 57 shorts and four actresses until “Alice in the Big League” on August 22, 1927. However, the cost and technical restrictions were the reasons the series was finally stopped.

At this time Charles Mintz an American film producer and distributor who had taken over his new wife Margaret J. Winkler’s business, she was the producer and distributor of the “Alice Shorts”, ordered a new series of shorts to be released under the Universal Studios logo. The studio wanted to get into the cartoon business and the result was the forgotten, to most non-cartoon buffs, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit might be considered the prototype for the future Mickey Mouse.

Created by Ub Iwerks and Walt. Oswald’s first appearance was in “Trolley Troubles” on September 5, 1927. Oswald was one of the first cartoon characters to have a definite personality and he used several different forms of humor to make people laugh such as physical, taking advantage of the situation he was in and frustration comedy. His personality to the alert movie goer was inspired by silent film star Douglas Fairbanks and Oswald possessed some of Fairbanks' characteristics too.

Let’s cross the continent and see what the completion was doing during these years besides creating those “Follow the Bouncing Ball” sound shorts.

Max and his brothers had a strong business sense and formed with Lee DeForest, Edward Miles Fadiman and Hugo Riesenfield “Red Deal Pictures Corporation” which would own 36 East Coast movie theaters to show the Fleischer’s product and increase their profit margin. Until the end of the Second World War almost every major motion picture studio would have their own chain of movie houses. Edward Fadiman produced a few small films with the Fleischer’s, but was the man behind the movie theaters. Riesenfield is the more interesting of the two partners. He was a composer and would write the scores for Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 “The Ten Commandments” and his 1927 “The King of Kings”. Along with the score for D.W. Griffith’s “Abraham Lincoln” in 1930 and assist with the music for the Fleischer’s “Song Car-Tune” shorts, or the “Follow the Bouncing Ball” sing a longs.

In 1926 “Red Deal Pictures” had to file for bankruptcy as a result of DeForest’s “Phonofilm” company having gone into bankruptcy ending the theater chain before it really got going.

In 1928 as their studio made the transition from Silent to Sound Cartoons the Fleischer’s revived the “Song Car-Tunes” as “Screen Songs” and the first “The Sidewalks of New York: was released on February 5, 1929 through Paramount Pictures. This was a relief for the Fleischer Brothers who had just experienced another Bankruptcy the previous year and as a result of coming out of it. “Inkwell Films” was no more, but the “Fleischer Studios” was officially born. Also the silent “Inkwell Imps” series in 1929 was replaced with the “Talkartoon” series. Working through Paramount seemed a blessing, but time would show otherwise.

The Max Fleischer innovative stamp was clearly upon some of the “Screen Songs.” Max dared to use Negro Performers such as Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong in non-stereotypical depictions of “blacks”. In some parts of these “Screen Songs” the performers were live and at others “Rotoscoped” images. The treatment of Negro performers by the Fleischer’s was winning praise.

The Fleischer’s praise in this area of race relations irked Walt who never considered himself a bigot. However, he had already been in trouble over the issue. The first of the comments that he was racist were being spoken.

The Fleischer’s praise in this area of race relations irked Walt who never considered himself a bigot. However, he had already been in trouble over the issue. The first of the comments that he was racist were being spoken.

Two of the successful “Alice Shorts” are described as follows:

“One such Alice cartoon, Alice's Mysterious Mystery (1926) features two cartoon characters who resemble members of the Ku Klux Klan. One of the villains drags a dog character into a room marked "Death Chamber" and pulls out a long strand of sausage. In "Alice and the Dog Catcher" she is leader of a club called the Klix Klax Klub, in where the kids wear paper bags with their faces painted on them over their heads.”

The question of Walt’s latent racism would come to the forefront in his 1946 film “The Song of the South” set right after the Civil War. The story about this film is the second part of my blog article below.

In February 1928, Walt went to New York to negotiate a higher fee per “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit” shorts which were being distributed by Universal Pictures to reviewer comments such as: “exceptionally clever” and “fine cartoon ingenuity”. The series was a major success and Walt, justifiably, thought his studio deserved a little more for them now. Charles Mintz not only told Disney he actually planned to reduce the fee he paid him, but that the Harman Brothers, Ising and Freleng from the Disney Brother’s animation staff were now under personal contract to him. Threatening Walt with taking these animators and starting his own studio. Walt stood firm and told Mintz he could have them.

Another unknown problem facing Walt Disney was that Mintz had sold the rights for Oswald to Universal Studios. The above named animators went to work making new Oswald cartoons for Universal Pictures. It would take 78 years until 2006 for “The Walt Disney Company” to acquire back the rights to “Oswald” from what was then “NBC Universal” in a trade for “ABC Sportscaster” Al Michaels. “The Walt Disney Company” as the owners of ABC Television where able to agree to the trade.

Another unknown problem facing Walt Disney was that Mintz had sold the rights for Oswald to Universal Studios. The above named animators went to work making new Oswald cartoons for Universal Pictures. It would take 78 years until 2006 for “The Walt Disney Company” to acquire back the rights to “Oswald” from what was then “NBC Universal” in a trade for “ABC Sportscaster” Al Michaels. “The Walt Disney Company” as the owners of ABC Television where able to agree to the trade.

Disney and Iwerks went back to work as Walt looked for new animators.

On May 15, 1928 a silent test film called “Plane Crazy” was shown to an audience, but Disney could not get a distributor. The film was notable because the lead character was not Mortimer Mouse as originally planned, but Mickey.

At this time there was an awkward, but to Disney perfect scenario occurring. Although Hugh Harman and Rudolf “Rudy” Ising were technically under contract to Mintz. Mintz had yet to form a studio and so they continued to work for Walt and with his head animator for 1928 through 1929 Ub Iwerks, because of their need for money. They would assist Ub in producing two animated shorts for Walt. The aforementioned “Plane Crazy” and a second Mickey Mouse short that also could not find a distributor “The Gallopin’ Gaucho”. At this point Harman and Ising dreaming of their own studio left to work for Universal on further Oswald shorts.

They always say the third time is the charm and Walt and Ub started work on another Mickey Mouse Cartoon, but this time with Pat Powers “Cinephone” system and with the assistance of animators Johnny Cannon, Les Clark, Wilfred Jackson and Dick Lundy the result opened on November 18, 1928. The cartoon was designed as a parody of the Buster Keaton film “Steamboat Bill Jr.” and was “Steamboat Willie” and the rest was history. What exactly pushed this sound cartoon ahead of both the Fleischer’s and Terry’s efforts I really don’t know! Perhaps as some say it was the fact that “Steamboat Willie” used sound for comedic purposes, or that it actually had more of a story. Whatever it was “The Disney Studios” would be called the “House that Mickey built” and he would appear in 130 films. Ten of which would be nominated for the Academy Award and one “Lend a Paw” would win the award in 1942.

On August 22, 1929 Walt Disney introduced one of his most popular series “The Silly Symphonies” starting with “The Skeleton Dance.” The cartoon was entirely drawn by Ub Iwerks and directed by Walt. It was considered a modern film example of medieval European “danse macabre” imagery. In 1994 it would be voted by 1,000 Animation Professionals as Number 18 of the 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time.

On August 22, 1929 Walt Disney introduced one of his most popular series “The Silly Symphonies” starting with “The Skeleton Dance.” The cartoon was entirely drawn by Ub Iwerks and directed by Walt. It was considered a modern film example of medieval European “danse macabre” imagery. In 1994 it would be voted by 1,000 Animation Professionals as Number 18 of the 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time.

Part Four: 1930’s “Betty and Disney’s Folly”:

This decade would see some changes at both studios and the creation of others in the field of animation.

This decade would see some changes at both studios and the creation of others in the field of animation.

Through 1929 the Fleischer’s “Out of the Inkwell” series had a dog character named Fitz who was a companion of Ko-Ko. In 1930 in the new “Talkartoon” series Fitz became Bimbo the Dog.

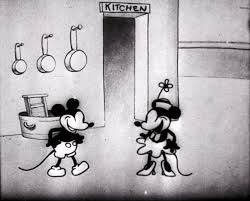

Koko and Fitz

Bimbo the Dog

Bimbo had a girlfriend who first appeared in “Dizzy Dishes” on August 9, 1930. She was an anthropomorphic Human-French poodle hybrid named Betty Boop.

Bettty would stay more dog like including dog ears and nose until June 9, 1933 when Max changed her completely into the form we know today in the short “Any Rags?” In that cartoon her floppy poodle ears became hoop earrings and her black poodle nose became a girl’s button-like nose. In 1932 the new look Betty Boop was given her own series which would last through 1939. However, the Fleischer’s had a problem with Betty and that was because she was a true sex symbol even if animated.

Koko and Fitz

Bimbo the Dog

Bimbo had a girlfriend who first appeared in “Dizzy Dishes” on August 9, 1930. She was an anthropomorphic Human-French poodle hybrid named Betty Boop.

Bettty would stay more dog like including dog ears and nose until June 9, 1933 when Max changed her completely into the form we know today in the short “Any Rags?” In that cartoon her floppy poodle ears became hoop earrings and her black poodle nose became a girl’s button-like nose. In 1932 the new look Betty Boop was given her own series which would last through 1939. However, the Fleischer’s had a problem with Betty and that was because she was a true sex symbol even if animated.

The cartoon “Minnie the Moocher” with Cab Calloway and his band playing that signature song placed Betty as a teenager of the carefree days of Jazz Age flappers. These cartoons were aimed at adult audiences and contained many sexual and psychological elements. Betty was also unique among female cartoon characters as she was a pure sexualized dog. I mean women. She also moved Paramount and the Fleischer’s into the number one cartoon position with Walt Disney a slightly distant second.

Max Fleischer’s attempts to get the cartoon rights to King Features Syndicate’s “Popeye the Sailor” finally paid off and the first film with that title appeared on July 14, 1933. To be certain the film would a success Max and Dave incorporated Betty Boop in it. She first did a Hula Dance on a carnival midway by herself followed by one with Popeye.

Everything seem perfect for the three brothers until 1934. The first attack came from "The National Legion of Decency", a multi-religious group originally founded by the Catholic Church, attacking the sexual nature of Betty Boop as a bad influence on children. Next the cartoon character got hit by the new “Motion Picture Production Code”. Although the code had been approved in 1930 it wouldn't go into actual effect until 1934.

The code is more commonly known for the man governing it Will H. Hays as the “Hays Office.” It was a set of industry moral censorship guidelines that governed the production of most United States motion pictures released by major studios from 1930 to 1968. Self created to avoid attacks by the Catholic Church and other religious groups over motion picture content. The studios, themselves, wrote the code without considering what might happen in the future to their own productions.

The code is more commonly known for the man governing it Will H. Hays as the “Hays Office.” It was a set of industry moral censorship guidelines that governed the production of most United States motion pictures released by major studios from 1930 to 1968. Self created to avoid attacks by the Catholic Church and other religious groups over motion picture content. The studios, themselves, wrote the code without considering what might happen in the future to their own productions.

The trouble "The Hays Office" caused the Fleischer’s came not directly by that office, but Paramount Pictures who released their shorts. The studio wanted no problems with the Hayes Office and from 1934 forward Betty Boop’s sexuality was eliminated and her clothing got longer. It was the end for the little “Jazz Baby” and the first of the major confrontations the Fleischer’s would have over their art vs their real needed cash flow and film distribution from Paramount.

A side note to what happened in 1934 to the Fleischers and others. Here are two examples of avoiding Hayes Office problems. Alfred Hitchcock found a way around the code for a scene in 1960’s “Psycho”. Actually he did it on purpose to get even with The Hays Office's interference in his productions. Up until that film you might see a bathroom sink or shower, but you never saw a toilet. Showing that particular item was a major no-no under the code. Obviously people just didn't need them, or knew what they were used for. Anyway, “Hitch” had a scene deliberately rewritten in "Psycho" showing Janet Lee ripping up documents and then flushing them down the toilet. There was no way around the scene as it was critical to the story line. So “Psycho” became the first film to show a complete bathroom under the Hayes Office Code enforcement and Hitchcock laughed all the way to the bank. Cecil B. DeMille also was able to get around the code by making all those "biblical" epics. Nobody including Will H. Hays would attack a motion picture based upon the bible even if it was filled with sex.

As I wrote earlier ex-Disney Animators Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising under their contract to Charles Mintz were now working at Universal Studio’s making the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series. In 1930 the two freed from their contract to Mintz moved to Warner Brothers to work under Leon Schlesinger. Sclesinger hired them because of the strength of the character Bosko the two had created back in 1928.

Their first project was to go after Walt’s successful “Silly Symphonies” and the ex-Disney animators created the first of the “Looney Tunes” cartoons. The name Schlesinger chose “Looney Tunes” was a direct parody of the name “Silly Symphonies”.

However, after three years the two would leave Warner’s and go to work at the Van Beuren Studios making cartoons for RKO Pictures. One additional year later the two moved again to MGM and began a series of Bosko cartoons as they had retained the rights to the character.

In 1930 Ub Iwerks left his friend Walt to try and start his own studio with Pat Powers backing him. The “Iwerks’ Studio” was never the success of either Walt’s or the Fleischers’ even though he had a contract with MGM. From 1933 until 1936 Ub produced a series of cartoon shorts in “Cinecolor” named “ComiColor Cartoons”. Also in 1933 Ub invented the “Multiplane Camera” out of spare parts from an old Chevrolet automobile. Leon Schlesinger would contract with Ub for four “Loony Tones” cartoons in 1937, but by 1940 Ub Iwerks would return to his friend Walt unlike the others who had left him and remain at Disney.

So what was actually happening at “The Wonderful World of Disney” as all this was going on elsewhere?

On November 18, 1932 Disney received a special Academy Award for the creation of Mickey Mouse. Originated by Walt and Ub Iwerks.

So what was actually happening at “The Wonderful World of Disney” as all this was going on elsewhere?

On November 18, 1932 Disney received a special Academy Award for the creation of Mickey Mouse. Originated by Walt and Ub Iwerks.

In 1932 Betty Boop became so popular that Max Fleischer was recognized as Walt’s major competitor and the feud gained momentum. Disney was concentrating on two series only. One was “Mickey Mouse” and other the “Silly Symphonies” that Leon Schlesinger was going after. What nobody knew at the time was the Walt had a plan and his first true dream for the future of animation and the Disney Brand. Since their creation Walt Disney had been using the “Silly Symphonies” as an experimental area in cartoon characterizations.

What would cause the second major run in with Paramount Pictures for the Fleischer’s and dubbed “Disney’s Folly” by the media was announced in the New York Times by Walt Disney in June 1934. The newly created “Walt Disney Productions” was going to make the first full length cartoon feature based upon the story of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”.

The next three years was devoted primarily to this project and a small production staff continued with the two animated series. What is considered to be the most famous of the Multiplane Cameras was invented by William Garity for the Disney Studios. It was used first in the “Silly Symphony” called “The Old Mill” which won an Academy Award in 1937 for Best Animated Short Film.

The camera would be put to major use in “Disney’s Folly” and because it can have different layers of artwork moving at different speeds the multiplane effect is considered a parallax process. A great example in “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” is when the Evil Queen drinks her potion and the surroundings appear to spin around her as she changes into the Old Hag. Shades of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” made a few years before in 1931 starring Frederick March.

The camera would be put to major use in “Disney’s Folly” and because it can have different layers of artwork moving at different speeds the multiplane effect is considered a parallax process. A great example in “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” is when the Evil Queen drinks her potion and the surroundings appear to spin around her as she changes into the Old Hag. Shades of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” made a few years before in 1931 starring Frederick March.

However, Walt’s wife and his brother Roy had little faith in his project and they attempted to talk him out of it. Walt had told the press his estimated cost to make the animated film would be approximately $250,000.00. He would have to take out a loan on his home and use other measures to help pay for the project that would not cost his estimated $250,000.00 to make, but at end of production the cost reached $1,488, 422.74.

“Snow White and the Seven Dwarf’s” premiered at the Carthay Circle Theater in Los Angeles on December 31, 1937. After its 1993 re-release the total gross for the film had reached an estimated $416,316,184.00. Walt’s “Folly” proved the critics and his family wrong.

At the 11th Academy Awards Walt Disney was awarded an honorary Oscar presented to him by Shirley Temple and the film was nominated for Best Musical Score. The World of Animation had changed forever.

While Walt had been creating his “Folly”. Things were not so perfect at the Fleischer Studios in New York City. The Brothers were having Union Labor problems and didn’t want to pay the cost. Max talked to Paramount and with their financial backing made the decision to move their operations. One would have thought after not doing it earlier. That now was a good time to move to Hollywood with all the major Motion Pictures Studios, but no. The "Bottom Profit Line" was first in Max’s mind and the studio moved to the non-union State of Florida where one could get a large piece of property for very little at the time.

The Fleischer Brother's problems with Paramount also continued. The new three-color Technicolor process became available. Max wanted to use it for both Betty Boop and Popeye. Paramount vetoed it based upon their concerns for “economic balance”, because of this "financial" concern by the studio's accounting department Walt would be able to use the process exclusively for the next four years.

As a result of obtaining the three-color Technicolor process. Walt started experimenting with it in shorts like “The Three Little Pigs” and some with Mickey Mouse such as “The Brave Little Tailor”, before committing it to “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” While the Fleischer’s continued to use black and white photography until 1934.

As a result of obtaining the three-color Technicolor process. Walt started experimenting with it in shorts like “The Three Little Pigs” and some with Mickey Mouse such as “The Brave Little Tailor”, before committing it to “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” While the Fleischer’s continued to use black and white photography until 1934.

In 1934 Paramount approved the use of only two color systems and both were based upon the inferior two strip process. One was the original two-strip Technicolor process that was based upon red and green. The other was “Cinecolor” based upon red and blue. The differences were clearly on the screen between what Disney produced and the Fleischer’s. In 1934 the “Color Classics” series was introduced as Max, Dave and Lou’s answer to the “Silly Symphonies”. So now both Paramount and Warner Brothers were chasing Walt Disney.

Again the innovative genius that was Max Fleischer came into play with their patented three-dimensional background effect called “The Stereoptical Process.” It was considered a distant relative of the multi-plane camera used by Iwerks and Disney, but it gave the Fleischer’s latitude. Max’s process went to work on a couple of extended Popeye cartoons in the two strip color process. They were “Popeye the Sailor Meets Sinbad the Sailor” in 1936 and “Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves” in 1937. However, it would take “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” to get the Paramount Executives to finally realize the value of animated films as the Fleischer Brothers had been telling them since they first went there.

Again the innovative genius that was Max Fleischer came into play with their patented three-dimensional background effect called “The Stereoptical Process.” It was considered a distant relative of the multi-plane camera used by Iwerks and Disney, but it gave the Fleischer’s latitude. Max’s process went to work on a couple of extended Popeye cartoons in the two strip color process. They were “Popeye the Sailor Meets Sinbad the Sailor” in 1936 and “Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves” in 1937. However, it would take “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” to get the Paramount Executives to finally realize the value of animated films as the Fleischer Brothers had been telling them since they first went there.

The Paramount Studio Executives wanted an immediate full length feature of their own. It was the spring of 1938 and the Fleischer’s were in the middle of building their Miami, Florida studio. The main part of the Walt Disney and Max Fleischer feud now occurred.

Simply put to maintain their normal output of animated shorts and make a full length feature film the Fleischer Brothers needed animators and the two employers with the most skilled were Leon Schlesinger and Walt Disney. So with Paramount’s money behind them they lured ex-Fleisher employees Grim Natwick, Al Eugster, Frank Smith and James Culhane at Disney to return home. From Schlesinger they took Cal Howard, Nelson Demorest, Joe D’Igalo and Tedd Pierce. Leon looked upon it as pure business, cut throat, but pure business. Walt considered it "Desertion" by his employees and "Theft" by Max.

Simply put to maintain their normal output of animated shorts and make a full length feature film the Fleischer Brothers needed animators and the two employers with the most skilled were Leon Schlesinger and Walt Disney. So with Paramount’s money behind them they lured ex-Fleisher employees Grim Natwick, Al Eugster, Frank Smith and James Culhane at Disney to return home. From Schlesinger they took Cal Howard, Nelson Demorest, Joe D’Igalo and Tedd Pierce. Leon looked upon it as pure business, cut throat, but pure business. Walt considered it "Desertion" by his employees and "Theft" by Max.

Because of the time restraints placed upon them by Paramount the Fleischer’s used a lot of “Rotoscoping” in “Gulliver’s Travels”. During pre-production the idea of using Popeye as Gulliver was discussed and scraped.

Compare the animation and color in this scene from "Gulliver's Travels on the left to one from "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" on the right. As an illustration of the problems facing the Fleischer Brothers due to Paramount's demands.

On December 22, 1939 the Fleischer film “Gulliver Travels” Directed by Dave and Produced by Max premiered. The film did very well at the Box Office and spun off two short lived cartoon series using four supporting characters from the film. The film was nominated for two Academy Awards: Victor Young for Best Music Original Score and Ralph Rainger (music) and Leo Robin (lyrics) for Best Music Original Song “Faithful Forever”. It won neither.

Compare the animation and color in this scene from "Gulliver's Travels on the left to one from "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" on the right. As an illustration of the problems facing the Fleischer Brothers due to Paramount's demands.

On December 22, 1939 the Fleischer film “Gulliver Travels” Directed by Dave and Produced by Max premiered. The film did very well at the Box Office and spun off two short lived cartoon series using four supporting characters from the film. The film was nominated for two Academy Awards: Victor Young for Best Music Original Score and Ralph Rainger (music) and Leo Robin (lyrics) for Best Music Original Song “Faithful Forever”. It won neither.

Part Five: 1940’s “ The Rise of Walt and the End of Max”

A second feud developed in house between Max and Dave after they moved to Miami in 1938. Dave had begun an adulterous affair with his secretary to the objection of Max and then this was followed by other personal and professional disputes. The family was in crisis.

A second feud developed in house between Max and Dave after they moved to Miami in 1938. Dave had begun an adulterous affair with his secretary to the objection of Max and then this was followed by other personal and professional disputes. The family was in crisis.

Flashback:

Prior to the start of production and the release of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” Walt Disney in 1936 had decided Mickey Mouse needed a popularity boast and what a boast it would end up being.

So while one team worked on the pre-production of the first feature length animated movie. Another started work on what was thought would be a deluxe length cartoon short based upon the poem written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and set to the orchestral piece inspired by the poem by Paul Dukas “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” starring the Mouse. However other events would place Mickey’s cartoon on hold for a short while. Until one day at Chasen’s Restaurant Walt met with Leopold Stokowski to discuss music in general and during the conversion the idea of bringing back “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” with Mickey was again raised.

On October 26, 1937 Walt wrote:

On October 26, 1937 Walt wrote:

“all steamed up over the idea of Stokowski working with us ... The union of Stokowski and his music, together with the best of our medium, would be the means of a success and should lead to a new style of motion picture presentation."

Animation on “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” what was still to be a single cartoon started on January 21, 1938, but by February the idea of making a multiple cartoon feature of classical music took hold. One year later on January 5, 1939 Stokowski and Disney had a minor disagreement over Walt’s idea of using mythology for the musical segment of “Cydalise.” Walt’s argument was based upon the pieces opening March called “The Entry of the Little Fauns”. Stokowski was concerned how the music critics might react to seeing mythological characters. The piece was eventually replaced by Ludwig van Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony with the same objection for Leopold.

July 1939 found agreement on creating a new revolutionary sound system for the music numbers. What had been previously called “The Concert Movie” was “Fantasia.” The budget now included an extra $200,000 the estimated cost for what was being called “Fantasound” a pioneering stereophonic surround sound system.

Animation on all the segments had been put in full production by the start of 1940. At that time Walt Disney Productions released their second full length animated feature “Pinocchio” on February 7, 1940. The film cost Disney $2,289,247.00 to make at the time and by June 2, 2009 the film had grossed $84,254,167.00. The soundtrack won the Academy Award for Best Original Score and Jimmy Cricket’s song “When You Wish Upon A Star” became the trademark song of the Disney Company to this day.

Meanwhile RKO Pictures that was releasing all of Disney’s films at this time was strongly against the idea of “Fantastia”. RKO's Executives thought the film would require an intermission as it's running time was two hours and eight minutes in length. They also described the film as “a long hair musical.” However, in a compromise to Walt they agreed to relax their exclusive distribution contract for the Road Show Engagement which would be shown in “Fantasound”, if Walt financed it himself.

“Fantasia” had a double World Premiere in the “Fantasound” process. The first was on November 13, 1940 at the Broadway Theater in New York City. The second was on January 29, 1941 at the Carthay Circle Theater in Los Angeles. For it’s time the incredible budget was $2.28 million dollars. As of April 13, 2012 Walt Disney’s “long hair musical” has grossed $83,320,000.00.

However, Leopold Strokowski was right. The music critics at the time hated it, but over time the film would find its audience and place in animated history.

The new War in Europe caused by Germany’s invasion of Poland resulted in both “Fantasia” and “Pinocchio” loosing large portions of their expected income. As a result unexpectedly Walt was in financial trouble. It was impossible to show the films in many European countries.

Luckily from the ticket sales for “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” Walt was able to build and complete the Disney Studio on Buena Vista Street in Burbank, California. Where the Disney Company still resides, before these troubles began.

Originally planned as a long short, but then turned into a full length film for the purpose of recovering the lost revenue from the two previous films. Walt turned to “Dumbo”. The film was released on October 31, 1941 at a cost of $950,000.00 and during its initial release made $1.6 million. However, the film was delayed for the very reason the Fleischer’s moved to Florida.

Union Leader Herbert Sorrell of the “Screen Cartoonist Guild” demanded that Walt sign with his Union. Walt had already signed with “IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) and told Sorrell that he would put the issue to a vote of his animation staff. Walt’s offer was not acceptable to Sorrell and on May 29, 1941, shortly after the rough animation for “Dumbo” was completed, much of the Disney studio staff went out on strike. Not only did the strike have an impact on the cost of the film, but it ended the “family” atmosphere at the studio forever and Walt Disney developed a pure “Executive” attitude toward his employees.

Even though the film was nominated for two Academy Awards and won the Best Scoring of a Musical Picture in 1941 and later after the war in 1947 the Cannes Film Festival award for Best Animation Design. “Dumbo” for the second time brought up racism and Walt Disney.

Some writers and critics looked at the crows as black stereotypes of the time. They also point out that the original name for script purposes of the lead bird was “Jim Crow”. The crows were played by members of the popular all-black “Hall Johnson Choir.” On the flip side Walt’s defenders including members of the African American Community point out that the Crows were the biggest supporters in the film of “Dumbo” and have the best song “When I See an Elephant Fly”. The call about Walt’s latent racism, or not is yours my reader and I will go more deeply into such charges in the second part of this article about the motion picture "Song of the South".

Some writers and critics looked at the crows as black stereotypes of the time. They also point out that the original name for script purposes of the lead bird was “Jim Crow”. The crows were played by members of the popular all-black “Hall Johnson Choir.” On the flip side Walt’s defenders including members of the African American Community point out that the Crows were the biggest supporters in the film of “Dumbo” and have the best song “When I See an Elephant Fly”. The call about Walt’s latent racism, or not is yours my reader and I will go more deeply into such charges in the second part of this article about the motion picture "Song of the South".

So how where the Fleischer’s fortunes going prior to America’s entry into World War 2 at this time in America's history?

As with the Disney Studio and RKO Pictures loosing overseas markets for their films. Paramount Pictures was also affected by the War in Europe which almost stopped their release of the Fleischer’s “Gulliver’s Travels” overseas. More importantly both that film's revenue and income from the Popeye Cartoons still playing in Europe were not being properly reported to the Fleischer’s Accounting Department. That fact became a major contributing factor to the building financial loss for the Brothers which they were entirely unaware was occurring..

Immediately after the success of “Gulliver’s Travels” the Fleischer’s started work on a second full length animated feature. At the same time another group of animators were working on the first of the costly “Superman” cartoons that would be released on September 26, 1941. The art work on the short was nominated for the 1941 “Academy Award for Best Short Subject: Cartoons.” Max and his brothers would loose to Walt’s Mickey Mouse short “Lend A Paw” one of the Pluto cartoons.

The cost of making that second full length feature known by either of three titles: “Mr. Bug Goes to Town”, Hoppity Goes to Town” and “Bugville” was climbing. Although having just moved to Miami and their new studio. The Fleischer’s were forced to sell it on May 24, 1941 to Paramount Pictures to cover costs of the cartoon’s production and their overly large staff of animators. A strange turn of events.

Their next problem was the planned release date for the film of November 1941. Walt’s “Dumbo” had only opened the month before and was doing solid business. So Paramount decided to move the Fleischer’s film to December 5, 1941 two days prior to “Pearl Harbor”. American’s were not interested in seeing a cartoon at the time. The film cost the Fleischer’s $713,511.00 and the Box Office would only be $241,000.00. A loss on the one picture of $472,511.00 on top of having to sell their new studio. Things for the Fleischer Brothers were definitely different than the Disney Brothers.

Prior to these events and the financial problems Disney experienced over “Pinocchio” and “Fantasia.” Walter Lantz, Paul Terry and Leon Schlesinger all had plans for feature length animated films. All three dropped them.

November 28, 1941 saw the release of the second Superman cartoon entitled “The Mechanical Monsters”. Work was already in progress on two more “Billion Dollar Limited” released January 9, 1942 and “The Arctic Giant” released February 27, 1942. The plan was to release one Superman short every month.

After the completion of “Mr. Bug Goes to Town” Max sent a telegram to Paramount explaining the internal problems he was having with his brother Dave. He said that he could no longer work with him. Paramount’s executives responded with letters of resignations for each of the three Fleischer Brothers. This in effect severed all control of Fleischer Studios from the brothers turning it over to Paramount. Dave meanwhile left for California to take over as head of Columbia Pictures “Screen Gems” unit. That single event allowed Paramount Studios, because of Dave’s Breach of Contract to take over Fleischer Studios.

The re-organization of the Fleischer Studios began. Officially the re-organization into “Famous Studios” would not be completed until May 25, 1942. However, Paramount immediately removed Max, Dave and Lou. Three top Fleischer employees were promoted to take over the new animation studio. Business Manager Sam Buchwald replaced Max as Executive Producer. Storyboard artist Isadore Sparber and Max’s own son-in-law head animator Seymour Kneitel took over the responsibilities of Dave as supervising producers and credited directors.

Paramount relocated the studio back to New York City, sold the Miami Property and downsize the staff. Under the Famous Studio name the last eight Superman cartoons would be made. The Fleischer Studio name and quality remained on the first nine through “Terror on the Midway” released August 26, 1942. The last eight would be of lower quality as Paramount had always deemed Superman too expensive to make. Originally Max had wanted a budget of $100,000 per six minute episode and Paramount negotiated it down to $50,000. Now that cost was cut yet again. These final eight Superman entries were mostly wartime propaganda and one even contained a cameo by Hitler.

After the Fleischer’s left Famous Studios continued for a while with both Superman as I have written and Popeye. In 1943 they would create a new series with the character of “Little Lulu” and another series called “Noveltoons” modeled after “Loony Toons” and “Merrie Melodies” which both had been modeled after Disney’s “Silly Symphonies”. That series would introduce “Herman and Katnip”, “Baby Huey” and a certain spirit “Casper the Friendly Ghost” among others.

Max’s rift with Dave never was resolved and lasted into the grave. Max next went to work for the “Jam Handy Organization” were he supervised technical training films for the Army and Navy. After the war he supervised the animated adaptation of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” in 1948 for the Montgomery Ward Stores. In 1955 Max lost a lawsuit over the removal of his name by Paramount on his cartoons they now completely owned. The judge said although the lawsuit had merit the Statute of Limitation had run out and he had no choice but to rule against Max. From 1960 to 1961 Max revived the “Out of the Inkwell Studios” and created 100 colored Ko-ko Cartoons for television.

As for what happened to Lou after demise of the studio. All I could find is a references that he voiced “Whimpy” in the Popeye cartoons and was the music director for the Fleischer Studios. Along with the sad fact that Lou died on October 16, 1976 which was my own 30th Birthday.

Our story is not over and we need to return to Walt and the Second World War and events entirely different than those faced by the Fleischer Brothers.

At the start of the war the “U.S. Army and Navy Bureau of Aeronautics” contracted most of the Disney Burbank Studio’s facilities staff to create training films for them. Such as “Aircraft Carrier Landing Signals” and home-front morale boosting shorts like “Der Fueher’s Face” which was originally to be titled “Donald Duck in Nutzi Land.” The short would win an Academy Award. Another Technicolor full length live action/animated film “Victory Through Air Power” received an 1943 Academy Award nomination for Best Music Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture. Walt had read Russian Aviation Pioneer and Inventor Alexander Nikolaievich Prokofiev de Seversky’s book of the same title and used his own personal funds to make the movie which included de Seversky himself. These type of films did not generate income, but did generate supporters for the Disney Company.

“Bambi” was released August 9, 1942 and under performed. It had a budget of $1.7 million and only made $1.64 million on its first release. However, as of January 2, 2012 the film has grossed over $267,447,150.00.

In 1941 the U.S. State Department sent Walt and a group of his animators to South America as part of its “Good Neighbor Policy” and at the same time guaranteeing financing for the resultant movie “Saludos Amigos” released August 24, 1942 in Rio de Janerio. The film starred Donald Duck in two segments, Goofy in one and introduced the character of Jose Carioca the Brazilian cigar smoking parrot. The film was so successful that two years later Walt would make “The Three Caballeros”.

In the mid-1940’s Walt was in now a position to continue work on two shelved films “Alice in Wonderland” and “Peter Pan”. Along with starting to develop “Cinderella”. A far different picture than Max and his Brothers had gotten themselves into.

1948 saw Walt move into another area of family filming with his first “True-Life Adventure” film “On Seal Island” which ran 27 minutes in length. The film was of seal life on a group of four volcanic islands off the coast of Alaska now called the Pribilof Islands that were known in 1948 as the Northern Fur Seal Islands. The nature film won the 1949 Academy Award for Best Short Subject, the 1949 Cannes Film Festival award for Best Documentary and was nominated in 1951 for the BAFTA Awards in the category of Best Documentary Film. A fine start for Walt Disney Productions.

Walt had also started in 1946 a series of “packaged films”, or to be precise more than one title under a single overall title. One of the most successful came out on October 5, 1949 entitled: “The Adventures of Ichabod and Mister Toad”. The film had two segments. The first was based upon Kenneth Grahame’s “The Wind and the Willows” and was narrated by Basil Rathbone. The second segment was Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” narrated by Bing Crosby.

Walt had also started in 1946 a series of “packaged films”, or to be precise more than one title under a single overall title. One of the most successful came out on October 5, 1949 entitled: “The Adventures of Ichabod and Mister Toad”. The film had two segments. The first was based upon Kenneth Grahame’s “The Wind and the Willows” and was narrated by Basil Rathbone. The second segment was Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” narrated by Bing Crosby.

Part Six: The End of My Story:

In 1953 Walt had an idea for a movie, but it required a Director who could not only direct actors but understood animation techniques. Walt knew who he wanted and he swallowed his own pride and asked Max’s son Richard Fleischer to direct “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea”.

This move led to Max and Walt becoming friends once more. However, according to Richard every time he mentioned Walt’s name to his father. Max would reply “That Son of a Bitch”.

No comments:

Post a Comment